pcond is a library to build "printable" predicates to build conditions that generate informative messages on failures of value checks.

Background

In programmings, checking a value if it satisfies a given condition is a common and wide-spread concern.

Is a value null or not?

Is a given number positive or zero?

Isn’t a string empty?

Does it have a length longer than a certain value?

And more.

For each of them, we want a proper error message on a failure. All of these can happen in a context of input value checking, a validation in API entry point, an assertion in unit testing, {pre,post}-condition checks in Design by Contract style programming.

However, especially in Java, there is no good uniformed solution to them.

For value checking in a normal product code, we may use Validate class[1] (Apache Commons), Preconditions class[2] (Google Guava), or just create our own class to check and compose error messages on failures.

For Unit Testing, classes are used for defining conditions to check the validity of values such as Matcher[3], Assert[4] or Subject[5].

For Design by Contract, some relies on annotations to define contracts[6], some other re-uses a test assertion library for it[7].

Every solution in every context above provides a user with a way to override messages that it generates by default because a library cannot always compose a sufficiently informative and helpful message automatically. But such hand-crafted messages tend to be stale easily over time and error-prone.

Thus, in spite that the same concern is observed among wide areas, no good uniformed solution has been provided and the concern is addressed in quite ad hoc manners depending on the contexts.

pcond is a library that provides a uniformed solution to all the use-cases above.

Key Concepts

Existing assertion libraries require users to define a message for a class under test. Following is an example presented in baeldung.com[13].

public class IsOnlyDigits extends TypeSafeMatcher<String> {

@Override

protected boolean matchesSafely(String s) {

try {

Integer.parseInt(s);

return true;

} catch (NumberFormatException nfe){

return false;

}

}

@Override

public void describeTo(Description description) {

description.appendText("only digits");

}

}If the type is a user custom class, which has multiple fields to be examined, the implementation will be complicated.[1]

This is the point, where we should stop and take a think. Isn’t there any better approach?

The general pattern we can see in custom defined matchers is that: It first transforms a given value into a type for which a check can be conducted and a message can be composed. This happens at once inside a matcher. So, users need to create an unmanageable number of matchers in the end.

Rather than creating a large number of matchers, what people tend to do is to write test code sacrificing readability of error messages. Following is a test picked up from a project called "ditaa"[17].

class TextGridTest {

@Test

public void testFillContinuousAreaSquareInside() throws FileNotFoundException, IOException {

TextGrid squareGrid;

squareGrid = new TextGrid();

squareGrid.loadFrom("tests/text/simple_square01.txt");

CellSet filledArea = squareGrid.fillContinuousArea(3, 3, '*');

int size = filledArea.size();

assertEquals(15, size);

// skipped...

}

}In this example, a value on which SUT operation should be performed is given at first (line 4-6).

When a functionality to be tested is performed (line 7), a value which we can do some check is extracted from it by calleing size() method (line 9).

Then, the value is checked if it satisfies a certain condition, in this case it euqals to 15.

When this test fails, we will need to go back and forth between the error message and the source code just to understand what is going on. Because the error message will show only a certain integer is different from 15, which will not be helpful.

Instead, why don’t we try to include the given value and how it was transformed into the value we do the assertion check.

In this example, the initial given value is squareGrid takes after line 6.

the transformation step is the procedure describle in line 8 and 9.

The value we do the assertionc heck is the value of size.

The combined step of this transformation and checking can be considered a predicate for the given value.

The approach pcond proposes is to let users compose a predicate to check all types from relatively small number of functions and predicates, which can give human-readable and meaningful message.

It doesn’t define its own "Matcher"(Hamcrest), "Assert"(AssertJ), or "Subject"(Google Truth).

Instead, it directly uses Java’s standard Function and Predicate.

In this section, following topics will be covered.

-

Transform-and-Check Programming Model

-

Printable & Composable Predicates

-

Entry-points:

Predicates,Functions, andPrintables -

Fluent API to build printable predicates

Hereafter, we just call "matcher"-like concepts in various assertion libraries just "matcher".

Transform-and-Check Programming Model

Among key concepts of pcond, the most important one is its "Transform-and-Check Programming Model".

Instead of having users define a custom "Matcher" for every condition that they can think of, it provides a mechanism to compose a transforming predicate from simpler functions and predicates.

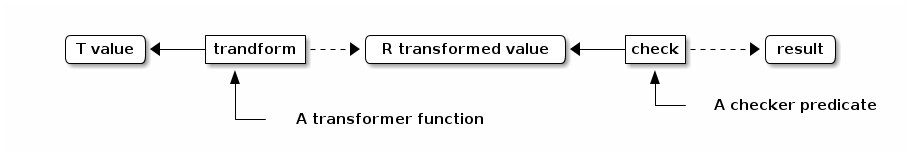

The Figure Transform and Check model’s pipeline: Transforming Predicate illustrates the concept of this model.

A transformer function transforms a given value of type T into a value of R.

This entire pipeline can be considered one predicate for value type T.

Thus, it can be used as a part of another transforming predicate, or vice versa.

Also, note that a function can be chained by Function#andThen method,

If both a transformer function and a checker function can generate a human-readable message, we would be able to compose a sufficiently informative message.

For instance:

-

Given

value, -

When transform is applied, it returns

transformed value, -

Then the check is passed/failed"

With this model, "a string 'hello' is longer than 10" can be expressed as follows:

-

Given

value:"hello", -

When

lengthis applied, it returns5, -

Then the

greaterThan[10]is failed"

This is still informative and understandable.

The remaining part is how to make transforming predicates render human-readable messages.

For instance, messages that Hamcrest renders becomes hard to understand when a failed condition is complex.

For the approach pcond takes to make it informative yet understandable, please check Printable & Composable Predicates.

Printable & Composable Predicates

If we desire to provide something more or less similar to power-assert in Java, we need a mechanism to make predicate and its runtime evaluation result programmatically accessible.[2]]

The ideas behind pcond 's approach are:

-

Checks programmers want to conduct can be modeled as a composition of simpler conditions. As discussed in the Transform-and-Check Programming Model.

-

It provides predicates composed from others, such as

not,allOf, andanyOf, so that a user can build any condition from simpler ones using the operators. -

A mechanism to compose a human-readable message to describe what happened when a check fails.

Following is an actual example to test if ExampleClass gives a proper message as a return value of salute method.

public class PcondExample {

class ExampleClass {

public String salute() {

return "Hello, I am " + this;

}

}

@Test

public void exampleTestMethod() {

assertThat(

new ExampleClass(),

Predicates.<ExampleClass, String>transform(call("salute", "Hello")) (1)

.check(allOf(containsString("Hello"),

containsString("ExampleType")))); (2)

}

}| 1 | It is suggested to explicitly specify type parameters, which are type before transformation and type after transformation.

In this case ExampleClass is an input to the transforming function and String is its output. |

| 2 | This check will make the test fail because the name of class under test is ExampleClass, not ExampleType. |

The library composes a following message on the failure for "actual" value part.

ExampleClass@12345 ->transform:<>.salute() ->"Hello, I am ExampleClass@12345"

"Hello, I am ExampleClass..."->check:allOf ->false

-> containsString[Hello] ->true

[0] -> containsString[ExampleType]->false

.Detail of failure [0]

---

Hello, I am ExampleClass@12345

---

Thus, you can see that both the test code and the message will be readable, informative, and structured without writing any redundant and error prone hand crafted message.

For the mechanism pcond implemented this, check Package com.github.dakusui.pcond.core

To the view of the author of pcond, the pain comes from the lack of introspection capability of Java.

If Java had the capability as other languages (e.g. JavaScript), you could implement a library like power-assert[12].

With that, just construct a predicate whatever you want and let it be evaluated.

It will print an error message like below:

1) Array #indexOf() should return index when the value is present:

AssertionError: # path/to/test/mocha_node.js:10

assert(ary.indexOf(zero) === two)

| | | | |

| | | | 2

| -1 0 false

[1,2,3]

[number] two

=> 2

[number] ary.indexOf(zero)

=> -1

If you try to build such a library in Java, you will need to resort to instrumentation, which delivers an intrusive usage manner. In fact, there exists a github repository that provides "power-assert" for Java; "power-assert-java". However, the library seems not to be maintained and the recent binaries aren’t available in public nexus repositories anymore.

Entry-points

As already discussed, an assertion is composed by connecting functions and predicates in the model.

Such functions and predicates should be relatively small number and reused across assertions.

pcond has built-in functions and predicates for users to save their time.

They are created by static factory methods defined in the entry point classes presented in this section.

It is recommended to static import those methods when possible for the sake of readability.

Predicates

Predicates is an entry-point class that holds methods to create re-usable predicates to examine a given value.

For instance, isEqualTo, greaterThan, greaterThanOrEqualTo, littleThan, etc.

Note that this entry-point class also has methods to create a new predicate from given ones, such as allOf, anyOf, and, or, and not.

allOf and and creates a new predicate of a conjunction of given ones (child predicates).

Similarly, anyOf and or creates a new predicate of a disjunction of them.

allOf and anyOf continue the evaluation of child predicates even if one of them results in false or throws an exception.

One important static factory method in this entry-point class is transform(String, Function<O, P>).

This returns a factory object to create a transforming predicate and check(String, Predicate<? super P>) is the method to create it.

Following is an example to use it.

import com.github.dakusui.pcond.forms.Predicates;

public class TransformingPredicateExample {

public void example() {

Predicate<String> p = Predicates.<String, Integer>transform("length", String::length).check("isGreaterThan[10]", i -> i > 10);

System.out.println(p);

}

}Note that sometimes Java compiler cannot infer appropriate types from the context around transform method.

It is a good idea to explicitly specify them when you see compilation errors around it.

Functions

To support custom types, it needs to provide a way to invoke a method whose name and arguments are given through parameters.

Functions.call(String, Object… args) is the method for this.

There is a few variants of this method such as Functions.call(MethodQuery) in `Functions entry point class.

Also it has several methods that convert a supported class into another.

For instance, length transforms a String to int by calling String#length method.

Functions returned by methods defined in this class can be connected by Function.andThen(Function) method.

Fluent API to build printable predicates

Nowadays, modern assertion libraries such as AssertJ[4] or Google Truth[5] has so called "Fluent" programming API, where method calls can be chained and your IDE can suggest next possible method call.

pcond also has similar API.

You can use it by starting xyzValue methods in Statement interface, where xyz will be one of string, double, float, long, integer, short, boolean, object, list, and stream.

Each of them returns a Transformer such as StringTransformer, which has appropriate methods to transform the value into the same or other supported value type.

Once transformation is done and to check if the transformed value is expected, you can call then method, which returns a Checker, which has available ways to check the value.

import Statement.stringValue;

public class FluentExample {

@Test

public void string_assertThatTest_failed() {

String givenValue = "helloWorld";

assertStatement(stringValue(givenValue)

.toLowerCase()

.then()

.isEqualTo("HELLOWORLD"));

}

}Configuration

pcond has a capability to configure some of its behaviors at runtime.

Such as choosing exceptions to be thrown on an assertion failure, number of characters for input value, action, and output value columns, etc.

For the further details, check Class com.github.dakusui.pcond.validator.Validator.Configuration.

Experimental Features

Currying

Currying is the technique of translating a function with multiple parameters into a sequence of functions, each taking a single parameterCurrying.

pcond employs this technique to construct an assertion that examines if a relationship between two or more collections.

With this feature, you can write a test like this:

public class NestCurryingAndContextExample {

public void example() {

assertThat(

Stream.of("Hi", "hello", "world"),

transform(nest(asList("1", "2", "o")))

// Experimentals.toCurriedContext

.check(noneMatch(toCurriedContextPredicate(stringEndsWith(), 0, 1))));

}

}This test is checking if no element in the first given list ("Hi", "hello, "world") starts with an element in the second list ("1", "2", "o").

For more details, check Package com.github.dakusui.pcond.core.

Cursor

It is a common situation, where you have a list of string tokens and you want to examine if they appear in another string in the order.

That is, you have a list ("hello", "world", "all") and they are found in a string such as "hello, Lisa, god’s in his heaven all’s right with the world.", which should fail because after world, all is not found.

We can think of a regular expression to check it, but on a failure, does it give us sufficiently informative message that indicates to which element the check has succeeded, etc.?

We can think of a similar check for a list, not a string, where ("hello", "world", "all") can be found in this order in a given list: ("hello", "all", "world", "network", "news")

With the cursor package’s functionality, you can build a test like following.

@Test(expected = ComparisonFailure.class)

public void givenSomeToBeFoundSomeNotToBe$whenFindElements$thenFailed() {

List<String> list = asList("Hello", "world", "", "everyone", "quick", "brown", "fox", "runs", "forever");

list.forEach(System.out::println);

TestAssertions.assertThat(list,

Cursors.findElements(

Predicates.isEqualTo("world"),

Predicates.isEqualTo("cat"), Predicates.isEqualTo("organization"), Predicates.isNotNull(), Predicates.isEqualTo("fox"), Predicates.isEqualTo("world")));

}This will print an error message as follows:

["Hello","world",""...;9] ->transform:toCursoredList ->["Hello","world",""...;9]

Cursors$CursoredList@f5f2bb7->check:allOf ->false

-> findElementBy[isEqualTo[world]] ->true

[0] -> findElementBy[isEqualTo[cat]] ->false

[1] -> findElementBy[isEq...[organization]]->false

-> findElementBy[isNotNull] ->true

-> findElementBy[isEqualTo[fox]] ->true

[2] -> findElementBy[isEqualTo[world]] ->false

[3] -> (end) ->false

.Detail of failure [0]

---

CursoredList:[Hello, world, , everyone, quick, brown, fox, runs, forever]

---

.Detail of failure [1]

---

CursoredList:[Hello, world, , everyone, quick, brown, fox, runs, forever]

---

...

Applications

pcond itself only has a capability to build predicates.

To use it as a DbC, value checking, or test assertion library, you need wrapper libraries.

pcond, thincrest-pcond, valid8j-pcond themselves are software products, which may evolve over time.

The programming interface of pcond can be modified over-time and it may introduce incompatibility between versions.

Here is a problem.

If thincres-pcond and valid8j-pcond were depending directly on pcond, what will happen?

Even if you only want to upgrade thincrest-pcond, which is used for test-side code, to a newer version, you may also need to upgrade valid8j-pcond, which is used for product-side code.

Because the new thincrest-pcond may depend on a newer version of pcond, which is not compatible with the pcond used by valid8j-pcond in the product side.

This is usually not acceptable.

So, those libraries take the following approach in Maven’s generate-source.:

-

Copy the source code of

pcondat the beginning of a build procedure. -

Move all the source file to a dedicated package. For

thincrest, all the source files undercom.github.dakusui.pcondwill be moved tocom.github.dakusui.thincrest_pcond. Forvalid8j, it will becom.github.dakusui.valid8j_pcond.

Thus, you can use different versions of pcond for thincrest and pcond for valid8j, independently.

Note that you need to be careful of the classes, which appear in both packages such as Predicates, Functions, or Printables, especially when you are working with thincrest-pcond in test-side code.

If you write test assertions using valid8j 's entry points, the error messages on a failure will become poor.

Because the message composing mechanism of thincrest-pcond can work with the pcond 's classes under the package for it (i.e. com.github.dakusui.thincrest_pcond).

For product-side codes, thincrest-pcond is not visible, but this is not vice-versa and valid8j-pcond is visible for thincrest-pcond.

This is why we human need to be careful of it.

References

-

[1] Validates, Apache Commons Validate class

-

[2] Preconditions, Google Guava Preconditions class

-

[3] Hamcrest, Matchers that can be combined to create flexible expressions of intent, Hamcrest

-

[4] AssertJ, Fluent assertions for java, AssertJ

-

[5] Truth - Fluent assertions for Java and Android, Google Truth

-

[6] Java DbC Java-DbC

-

[7] valid4j valid4j

-

[8] java-power-assert https://github.com/jkschneider/java-power-assert

-

[11] "Design by Contract, by Example" by Richard Mitchell and Jim McKim, 2002, Jim McKim, Richard Mitchell

-

[12] power-assert https://github.com/power-assert-js/power-assert

-

[14] Efficient JSON serialization with Jackson and Java blogs.oracle.com

-

[15] Currying - Wikipedia Currying

-

[16] Design by Contract - Wikipedia Metamorphic testing

-

[17] TextGridTest in ditaa project TextGridTest